The private rooms at Salvation Army’s Centre of Hope have

provided former dairy farmer Graham Chesney with privacy,

stability and a sense of community.

The private rooms at Salvation Army’s Centre of Hope have

provided former dairy farmer Graham Chesney with privacy,

stability and a sense of community.

“The difference between my room and the dorm is like night and

day,” says private room resident Graham. “It gives me privacy. A

chance to get into my own head.”

“The difference between my room and the dorm is like night and

day,” says private room resident Graham. “It gives me privacy. A

chance to get into my own head.”

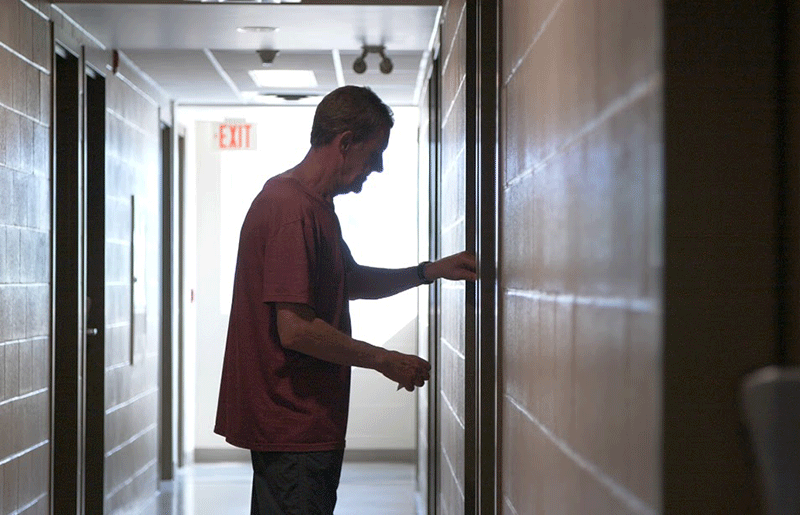

“The simple motion of being able to lock a door means so much,”

says registered social worker Colleen Parsons.

“The simple motion of being able to lock a door means so much,”

says registered social worker Colleen Parsons.

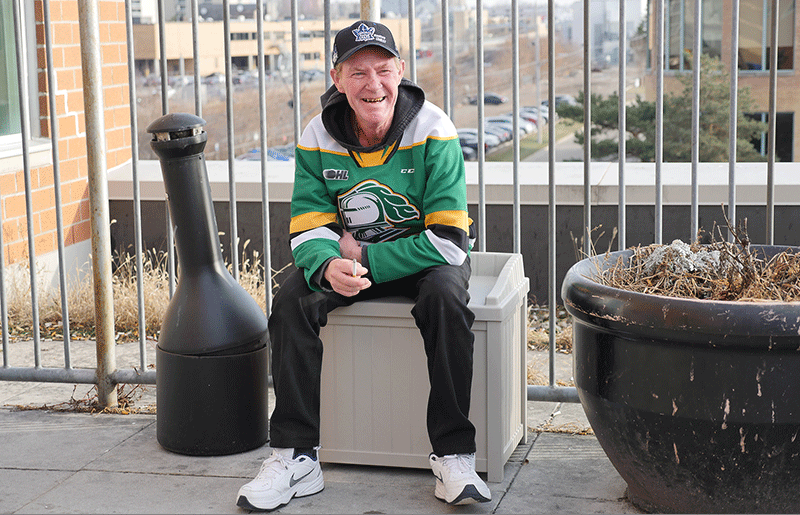

Private rooms residents have access to a balcony where they can

relax and gather their thoughts in privacy. Shown here: Researcher

Colleen Parsons and resident Graham Chesney.

Private rooms residents have access to a balcony where they can

relax and gather their thoughts in privacy. Shown here: Researcher

Colleen Parsons and resident Graham Chesney.

February 24, 2020

Private rooms provide space to heal and plan for the future

Graham Chesney’s room is tiny. The impact of this 38m2 space is huge. Here, Graham has his own bathroom, a place to store his belongings — and, best of all, a door.

His room is one of 66 private, transitional rooms at the Salvation Army’s Centre of Hope in downtown London, Ontario. He pays $500 per month and can make use of all the services offered by the Centre, such as meals, court services, and financial supports.

Graham is grateful for the opportunity — especially after spending a few months sleeping in the Centre’s emergency shelter dorms. The dorms typically sleep 4 to 6 residents. There is frequent turnover and residents are often dealing with a wide range of mental health issues and behaviours.

“The difference between my room and the dorm is like night and day,” says Graham. “It gives me privacy. A chance to get into my own head. I don’t have to worry about getting stuff stolen.”

A former dairy farmer, then construction worker, Graham was badly injured when he fell from a building while installing siding. Chronic back pain and subsequent addictions are factors that led him to the Centre in August 2018.

Offering private rooms to residents at the Salvation Army’s Centre of Hope is helping them heal and plan for their future.

The stability and continuity of the private rooms also creates a sense of community for Graham and his neighbours.

“We get to know each other. We’ve made some close relationships, and we help each other out. I feel safe here.”

The private rooms were created in 2004. Shelter staff have seen firsthand improvements in the health and mental wellbeing of residents. Until recently, the evidence was purely anecdotal and undocumented.

New research from Western University’s Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing has changed this. In 2019, the university began to document the experiences of the people who have used the private rooms. It’s looking at which aspects of the private rooms model work best and how they might be improved.

Most of the data for Phase 1 of the study was collected in face-to-face interviews with 16 private room residents.

“For us, it was important to capture people’s voices — the human complexity of their lives, the desires they have for housing and the impact of the private rooms experience and the supports offered,” says Dr. Abe Oudshoorn. Dr. Oudshoorn is the project’s lead researcher and assistant professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Western Ontario.

An overarching theme was the positive impact of the privacy that the rooms offer. Residents said it was key to helping them transition to more stable housing. They also reported an increase in overall health, stability, motivation, self-esteem and sense of dignity.

“We heard that the private rooms helped people to move forward in life,” says Colleen Parsons, registered social worker and research associate on the project. “The simple motion of being able to lock a door means so much.”

The study also made recommendations for improvements.

Residents said that being able to have small appliances in their room would allow them to prepare simple meals. They also suggested extending the 1-year maximum stay allowed in the private rooms. Many felt the deadline was unrealistic and created undue stress, given the long waiting list for affordable housing in London.

The Centre of Hope is already applying what it learned from this demonstration project.

In January 2020, it opened a new floor of rooms, specifically for people in recovery. It includes an internet café, appliances and a games room, among other improvements. The Western University researchers have already begun to track its success with Phase 2 of their research project.

“We want to find out how staying in private rooms impacts people’s recovery journey. We’ll be gathering data from the residents at various stages throughout their stay. We’re looking for real-time, rapid feedback, so that we can take an iterative approach to improvements,” says Dr. Oudshoorn.

In the meantime, Dr. Oudshoorn and his team, including co-investigators Dr. Carrie Marshall and Dr. Deanna Befus, are showcasing the results of Phase 1.

They produced long and short videos featuring interviews with the residents. They also prepared a guide with practical resources to help other settings implement the innovative model. Now they are sharing their knowledge at major conferences and through national housing and homelessness networks.

Their hope is that the private rooms model can be replicated in other communities across the country. If so, more people like Graham may get the help they need to transition to more permanent, stable affordable housing.

Phase 1 of the Transforming Emergency Shelter into Affordable Housing with Support (ON) project received funding through Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Demonstrations Initiative. This National Housing Strategy program showcases innovative practices, technologies, programs, polices and strategies with a goal to improve the performance, viability and effectiveness of affordable housing projects. This project is a collaboration between The Salvation Army Centre of Hope, and Western University’s Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing and the Centre for Research on Health Equity and Social Inclusion.

More information NHS Project Profile